.

CETA Artists Employment • Overview

In 1973, economic conditions in the U.S. were deteriorating. Growth was

stagnant and inflation was at record levels (this combination came to be

called “stagflation”). Consequently, the unemployment rate was stubbornly

high. In response, a bipartisan effort in the U.S. Congress brought about

the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), which was signed

into law by Richard Nixon in December, 1973. It would become the largest

federally funded employment program since the New Deal. It trained or

employed as many as four million people per year during its peak period 1977-80.

Unlike the New Deal, which included dedicated artist employment

components such as the Federal Artist Project (under the Works Progress

Administration), it was not envisioned that CETA would be used to employ

artists. In fact, its first program (named Title II) was dedicated to job training

rather than public sector employment. But it was soon followed by Title VI,

which was designed to provide jobs to well trained individuals in fields

suffering chronic unemployment. This opened up CETA to employingartists,

a fact that was quickly recognized by John Kreidler - an intern for the

San Francisco Arts Commission who had previously been an analyst at

the Department of Labor in Washington DC during the crafting of the CETA

legislation (and who had also studied the New Deal while in graduate school).

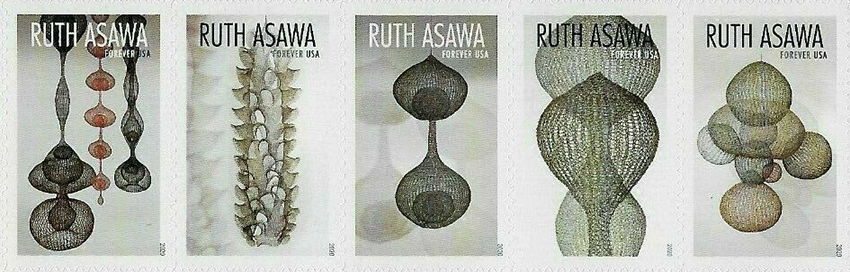

Kreidler found allies in city government as well as in the community arts sector

(such as artist Ruth Asawa, a member of the San Francisco Arts Commission

who

was directing the Alvarado School Art Workshop).They wrote a proposal that

resulted in the hiring of 24 artists under CETA. The city was so pleased with

theinitial results that it

quickly approved an additional 90 artist positions,

employing artists in the Workshop, the Neighborhood Arts Project, and a

variety of city agencies. The number eventually grew to 130.

Ruth Asawa worked closely with John Kreidler in

securing

CETA funding for both the Alvarado

Workshop and the Neighborhood Arts Project.

It should be noted that this initiative could happen at the city level

because CETA — unlike the New Deal programs — was designed to be

decentralized, with funding going to states as block grants, which were in

turn directed to counties, municipalities and other “prime sponsors” who

could then design their own programs for use of the funds.

Word about CETA’s potential for funding arts jobs got around quickly —

first to other communities in the Bay Area, then throughout California and

Washington State, and then to cities like Dallas, Chicago and Minneapolis/St. Paul.

With the advent of the Carter administration, funding for CETA increased dramatically

and a new Title (VII) was added. Additionally, the design and implementation of

CETA artist projects became more regularized, as they were brought under the

guidance of the Department of Labor (and specifically, Assistant Secretary for

Employmentand Training, Ernest Green, who strongly supported them).

Following this expansion of CETA, several additional artist-employment projects

were launched during 1977. Among these was Arts DC in the national capital,

which, during its five-year run, was especially successful in moving artists into

regular employment after their CETA stints, achieving a placement rate of 70%. Other

projects included Philadelphia, Atlanta, New Haven, and Milwaukee.

Then, in 1978, five large projects began in NYC employing, among them,

500 artists. The largest of these was sponsored by the nonprofit Cultural

Council Foundation. It hired 300 artists in various fields (visual, literary

and performing) and 40 artist administrators who would coordinate the

placement of artists into community service positions. The CCF CETA

Artists Project benefited in particular from the experience of several years

of prior projects around the country and a full year of development under the

guidance of the Department of Labor, the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs

and arts advocacy groups like the New York Foundation for the Arts. One

of the innovations of the CCF project was the inclusion of a documentation

unit (three photographers, three writers and an archivist/coordinator);

consequently, it is the best documented of all the CETA arts projects.

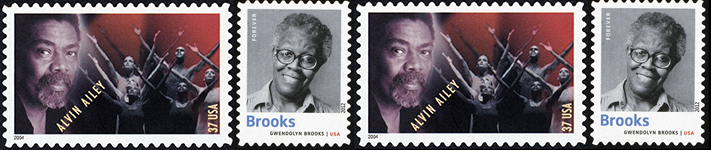

The Alvin Ailey Dance Company and the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago,

where Gwendolyn Brooks taught, received CETA funding.

It is estimated that, during the years 1974-82, CETA funded about 10,000

artist jobs and another 10,000 jobs in arts institutions such as museums,

theaters and other nonprofits. This was a small fraction of the total number

of CETA jobs, yet it was a vey large number of arts jobs when seen in

historical context. For comparison, in the 1930s, Federal One, the primary

artsemployment program of the New Deal, employed about 40,000 visual,

literary, musical, and dramatic artists in its various projects.

Another way to understand the significance that this funding had for the arts

is to look at the sums involved: CETA channeled about $200 million per year

into the hands of individual artists, arts organizations, and community partners.

(This would be $1 billion per year in 2025 dollars.) In comparison,

the annual budget of the National Endowment for the Arts

during that period averaged about $130 million.

CETA was wound down during 1981 and 1982, and was fully terminated in 1983

as its closure was a priority of the incoming Reagan administration.

Why is CETA’s large-scale employment of artists so little known in

comparison with the New Deal programs even though it happened much closer

to the current time? There are several reasons. One is that, unlike the New Deal,

CETA had no central administration and there is no central repository for its records.

Another is that most of the work done by CETA artists was incommunity service

and not in the production of public works, so its traces are more ephemeral.

And perhaps most important, CETA itself — a federal program that trained and

employed millions of people — was not part of a major PR campaign in the same

way that Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal programs had been.

One of the clearest legacies of CETA is the role it played in growing and stabilizing

community arts organizations and nonprofits in cities around the country.

In Philadelphia, for example, CETA covered five administrative lines for the

Painted Bride Arts Center (they were its first paid administrators) allowing it to grow

from a precarious artists’ collective into a major contributor to Philadelphia’s

cultural environment over the next several decades. CETA supported the creation

of the Penumbra Theater in St. Paul. It went on to become one of the premier

venues for Black dramatic arts in the U.S. producing many plays by the

esteemed playwright August Wilson.

Playwright August Wilson went to St. Paul Minnesota to join Penumbra Theater,

founded by Lou Bellamy in 1976 with CETA funding.

Another clear legacy of CETA is its role in nurturing the careers of many artists who went

on to substantial recognition. Dawoud Bey, for example, considered to be one of the

foremost artist photographers in the U.S. (and a MacArthur Fellow) was part of the

CCF project in NYC. His community assignment for two years was carrying out

his “Harlem U.S.A.” project under the auspices of the Studio Museum in Harlem,

which then gave him his first solo exhibition. Peter Coyote and Bill Irwin, who have

achieved considerable acclaim as performers, worked under CETA in San Francisco.

One can also consider CETA’s contribution to diversity in the arts. CETA arts projects,

in general, were far more diverse than was the norm in the 1970s in terms of race,

gender, age, even physical ability. They were certainly more diverse than the typical cohorts

of

NEA grant recipients. This was due in part to the hiring requirements put forth

by the Department of Labor; another factor was that CETA project creation and artist

hiring practices were well outside the arts establishment’s purview.

• Homepage • Legacy Project • NYC Project • Promoting CETA Arts History • Resources •